Queer Coding of Villains in Disney Movies

- Jason Russo

- Apr 28, 2020

- 13 min read

INTRODUCTION

Queer-coding of fictional characters is a common trope applied widely throughout American media (Kim, 2007). The premise of queer-coding is that characters are given stereotypical queer mannerisms or characteristics without outright confirmation that those characters actually belong to a sexual or gender minority. These mannerisms are usually gender transgressions (i.e. male characters speaking with higher pitched voices or female characters wearing traditionally masculine clothing), but can also manifest in the way they are dressed or the motivations governing their character arc (Kim, 2007).

While the trend is still prevalent today, twentieth century movies and television shows are particularly susceptible to this practice. This is largely due to the introduction of the Hays Code in 1934 which was a set of rules and regulations enacted to restrict what could be shown on mass-produced films (Mendoza-Pérez, 2018). Essentially, the code banned the production of any film with taboo subjects, nudity, or any content that could be deemed outside the normative moral standards of the time (Mendoza-Pérez, 2018). While the code did not explicitly ban LGBT content, it restricted film studios to the production of motion pictures that upheld “correct standards of life” and “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” while also banning films that portrayed “low forms of sex relationships” (Mendoza-Pérez, 2018). This effectively curbed the outright labelling of characters in films as members of a sexual minority. However, this didn’t stop movie producers from generating characters who audiences (either consciously or unconsciously) perceived as queer. As the Hays Code became even more strictly enforced during the start of the Cold War, an influx of queer-coded characters sprung up in American cinema (Hall & Almendarez, n.d.). Queer-coding was an easy way for filmmakers to make a character instantly othered and understood as being different, either for comedic relief or in order to demonize a character who threatened the status quo (Kim, 2007). Because queer culture itself was considered a “threat” to society at the time, queer-coding became a highly effective way of coding villainous characters to be instantly recognizable as devious or threatening to the average American. It was particularly effective in children’s media whose characters are often caricatures with largely exaggerated features and mannerisms (Kim, 2007). This proved to be a relatively common place to find characters who are queer-coded.

Walt Disney Studios is the largest producer of children’s media in the world, so it is a logical place to investigate sources of queer-coding (Watson, 2019). Disney villains in particular are some of the most obviously queer-coded characters in modern cinema. Some of the most iconic Disney villains, like Ursula from The Little Mermaid, Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty, and Scar from The Lion King are all notable examples of Disney villains who have been interpreted as queer by audiences (Allen, 2019). Interestingly, these queer-coded villains are equally as memorable as they are frightening to younger audiences. The conflation of fear with queer stereotypes suggests the possibility of a connection being drawn between these two characteristics, and ultimately, a harshening of gender stereotypes and latent homophobia.

Analysis of queer-coding has been conducted on various aspects of the media. Most research focus specifically on a certain character or movie franchise, like the analyses by Ásta Karen Ólafsdóttir (2014) and Hutton (2018) who analyzed the characters in John Waters films and representations of the Joker from various Batman revivals, respectively. The analysis conducted by Vujin and Krombholc (2019) was very insightful for my project as they looked at the representation of villainous characters in Harry Potter, like Lord Voldemort and the Boggart. The application of queer-coding to gender politics and sexism is highly important to the analysis of my project. The most useful study was conducted by Giunchigliani (2011) who analyzed Pixar villains and whose coding system I adapted for this analysis. However, all of these analyses have been conducted in fields outside of Psychology, so their interpretations are slightly different.

PURPOSE/IMPORTANCE

The purpose of this project is to analyze the instances of queer-coding in Disney villains in order to highlight how widespread the trope has been used in some of the most popular films of the past 70 years. While queer-coding is a recognized trope, it is not one that has often been studied empirically. Collecting data for this analysis cold provide much more detail to the extent of the use of trope as well as suggestions for how these representations may affect viewers. I expect to find a high number of instances of queer coding, especially in some of the older films. I hope to parse out more specific ways that villains have been queer coded, and also the ways that they have not been queer coded as both could be highly illuminative as to the ways that characters are digested by American viewers. I do expect to find that more modern villains are slightly less queer coded, and that there may be great variation overall in the data.

This project is important because we know that media has a significant impact on people’s perceptions of society and the world around them. Children are especially susceptible to constructing their opinions of gender roles and sexuality based on the media that they view (Shafer, et al., 2012). The media practice model and the drench hypothesis both show the importance of accurate queer representation and how damaging it can be for queer adolescents to consume media where gender roles do not align with their individual expression (Mastro & Greenberg, 2000). This project will uncover the prevalence of those representations and hopefully break down some of the messages implicit with their consumption.

METHODS

For my archive, I used popular children’s animated Disney films from the past 70 years. As a selecting factor, I chose the top 24 scariest Disney villains based on a poll from the International Movie Database (IMDb) which generated 6,633 results (Maverick22, n.d.). Prior to looking at the individual villains listed, I developed a coding system based on three primary categories: Western normative gender roles, villainous traits, and Western queer stereotypes (separate criteria for male or female characters). I adapted this coding system from the one used by Giunchigliani (2011) which also analyzed queer-coding of villains in Pixar movies. I altered some of the criteria to better fit my project and added a section for female characters who were not included in Giunchigliani’s analysis. A list of the categories scored is provided in the graphs in the results section. During the coding process, I viwed video clips from each of the films in order to gauge the mannerisms of each characters and find their central motivations and basic physical descriptions.

I collected the data in an Excel spreadsheet which was a series of “yes”, “no”, and “N/A” responses. I counted the total number of each responses and then plotted them in four separate bar graphs which are included in the results section in order to view the data more easily.

RESULTS

The total list of characters and the films they were featured in is provided below.

DISCUSSION

The data collected showed a wide range of responses to the various coding criteria. Figure 1 displays that the majority of villains failed to meet five out of the seven gender roles typically expected of individuals in society. All 24 villains were shown to not be morally upright which was expected, but could also be another connection between queerness being perceived as immoral. As expected, most of the villains overwhelmingly scored with “yeses” for villainous traits in Figure 2 which confirms their casting as devious or evil within their films along with few or no redeeming characteristics.

Figures 3 and 4 are most interesting and pertinent to this research as they directly deal with queer-coding. Figure 3 represents queer coding for the male villains. Coding revealed that all 15 male villains lacked a steady romantic partner that would qualify them under a certain sexuality. The same was true for the majority of female characters, as well, with the exception of the Queen of Hearts from Alice in Wonderland. The Queen of Hearts is an interesting example of queer-coding because she is the only Disney villain included on the list to have a partner who is featured directly in the film alongside her. The animators chose to make the Queen very large with highly masculinized features. She is animated almost exactly as a male character would be, with the exception of feminine attire. She bears many stereotypical male characteristics: irritability, ferocity, brute strength, an affinity for violence, and a voice deeper than her husband’s. This is highly contrasted by him because he is starkly feminized. He is half the Queen’s height wearing feminine attire and his voice is pitched higher than the Queen’s. These details are important because this is one of the most obvious queer-coded representations of the characters studied. The Queen is made more of a threat to Alice and to society via her queerness and is deemed so insane by the film that she can only exist in Wonderland, a figment of Alice’s imagination. Her and her husband’s queer representations only exist to further highlight the absurdity of Wonderland which is a damaging message to send about gender roles as it underscores the concept that their behavior and appearance is somehow wrong. Alice is the only one to escape Wonderland, and her gender performance is exactly in line with expectations for girls, while the queer characters of the tale are destroyed in her mind.

Much like the King, the majority of male characters had higher pitched voices than their hero counterparts; however, this trend was even more prevalent among female characters whose voices were often much deeper. The most interesting example of this besides the Queen of Hearts is Ursula from The Little Mermaid. She is a unique character because she was modeled after the drag queen Divine, so her representation is one of the most obvious embodiments of queer culture (Acuna, 2019). Her exaggerated makeup and facial features coupled with her voice are quite starkly akin to those of drag performers (Acuna, 2019). By making her a villainous character who seeks to steal a woman’s (Ariel’s) voice is a direct signaling that queer individuals are a threat to non-queer people. No Disney heroes have been modeled after drag performers, so there is nothing in the Disney archives to challenge this assertion.

Both male and female villains used language more typical of the opposite sex. This was one of the hardest categories to code as language is very subjective, and much of language is inferred by inflection. But, overall, eight of the female characters were more assertive in their language with harsher diction and more curt phrasing, while nine of the male characters spoke with more rounded words and more seductive and eloquent inflection.

The ways in which the characters carry out their evildoings is also worthy of analysis. By normative Western standards, male characters are the heroes who are strong and do the fighting and “get their hands dirty”, while female characters are more reserved and use their charisma or cunning to get what they need. Interestingly, female villains were more likely to “get their hands dirty” when it comes to violence, action, or taking what they want. This casts them as more assertive and possibly more threatening to men. Male villains, on the other hand, are more likely to behave in feminine ways of using deception instead of brute strength to get what they need, implying that they are perhaps not strong enough and thus not manly enough to take what they need by force.

While these ways of queer-coding are interesting, what is also interesting is the ways in which animators decided not to queer-code characters. Very few male and female characters wore attire typical of another gender, or used cosmetics in a way not concordant with their perceived gender. Almost all of the women wore makeup (albeit very exaggerated in some cases) and none of the men wore makeup. In general, their clothes were typed with the gender that they were representing. The key element of queer-coding is that it is subtle enough to be noticed, but not be so overt that it becomes ridiculous or easily spotted by an untrained eye (Mendoza-Pérez, 2018). It is possible that these two characteristics would have made the characters entirely too queer and thus too threatening to pass the Hays Code or be palatable to mainstream society.

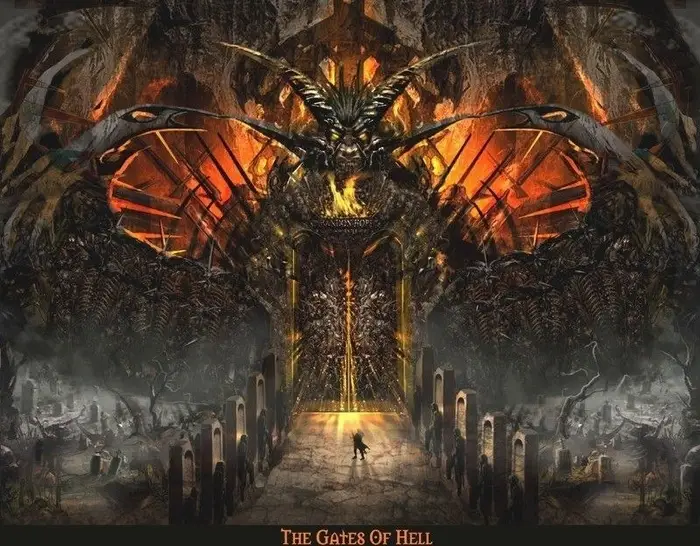

There are three villains who are almost entirely not queer-coded: Chernabog, The Horned King, and the Hydra. These three villains are all demonic characters. Chernabog and the Hydra do not speak at all, and serve as relatively minor villains in the films they are featured in. All three are more “traditional” villains in that there is little to no comedy or absurdity in their characterization; all three are representations of pure evil and barely exhibit any gender typed behavior at all as almost all of their screen time is devoted to violence or action. There is little or no material to code as queer as their characters are meant to be terrifying on their own and do not need to be queer-coded in order to be othered. Their demonic nature is sufficient enough.

Overall, the results were slightly weaker than I expected. Some of the characters were not as strongly queer-coded as I had anticipated them being. Besides this, I think the data was still enlightening as to the scope of queer coding in children’s cinema. Much of this relates back to our course topics concerning media theories and how the media reinforces gender roles and queer stereotypes. As mentioned in the purpose/importance section, both the drench hypothesis and the media practice model support why proper queer representation is important for young queer kids. The drench hypothesis states that individuals relate to characters they see in the media, and, subsequently, they are more likely to be influenced by the characters they relate to (Mastro & Greenberg, 2000). Applying that theory to queer-coding, queer kids may be more likely to relate to queer-coded characters because they share the commonality of being queer. However, if the only representation of queerness these children are seeing is of villains like the ones in this study who are all deeply flawed, often violent, and always social outcasts, this sends the message that that is all queer people can be in society. Similarly, the media practice model also reinforces this concept. This model is usually applied to children and adolescents, and it states that an individual’s characteristics influence what media they consume, but that media, in turn, also influences their mentality and identity. Media experience is filtered through the viewer’s lived experience and personal method of interpretation, but lived experiences and methods of interpretation are also affected in a circular fashion by the media they consume (Shafer, et al., 2012). Essentially, as it relates to this study, queer children are more likely to seek out media that feature queer characters, and then, those queer characters can influence their own self-concept and perceptions of the world. This is truly dangerous if the only representation these children are receiving is of the villains of a story like Ursula, Scar, or Maleficent and not heroes like Ariel, Simba, or Princess Aurora. It is important to constantly reevaluate the media being sold to us and our children as it clearly contains instances of representation that may be less than desirable for our children to be viewing and internalizing.

Works Cited

Acuna, K. (2019, July 15). How “The Lion King” codirector, a drag queen, and one of Disney’s greatest animators helped bring “The Little Mermaid” villain to life. Retrieved April 27, 2020, from https://www.insider.com/the-little-mermaid-ursula-concept-art-2019-7

Allen, S. (2019, July 17). I Miss Disney's Queer-Coded Villains-But the Next Generation Won't. Retrieved March 7, 2020, from http://www.newnownext.com/disney-queer-coded-animated-villains/07/2019/

Ashman, H., Donley, M., and Musker J. (Producers), & Clements, R. and Musker, J. (Directors). (1989). The Little Mermaid [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Ashman, H., et al. (Producers), & Trousdale, G. and Wise, K. (Directors). (1991). Beauty and the Beast [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Ásta Karen Ólafsdóttir, Á. (2014). Heteronormative Villains and Queer Heroes. Hugvísindasvið . Retrieved from https://skemman.is/bitstream/1946/18100/1/Heteronormative Villains and Queer Heroes - Queer Representation in the Films of John Waters by Asta Karen Olafsdottir.pdf

Betts, L., et al. (Producers), & Cook, D. (Director). (2004). Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The Three Musketeers [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Bradley, B., Hefner, V., & Drogos, K. (2008). Information-Seeking Practices during the Sexual Development of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals: The Influence and Effects of Coming Out in a Mediated Environment. Sexuality & Culture, 13, 32–50. doi: 10.1007/s12119-008-9041-y

Clements, R., et al., (Producers), & Clements, R. and Musker, J. (Directors). (1992). Aladdin [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Clements, R., et al., (Producers), & Clements, R., and Musker, J. (Directors). (1997). Hercules [Film]. Walt Disney Producers.

Coats, P., Garber, R. S., and Haaland, K. (Producers), & Bancroft, T. and Cook, B. (Directors). (1998). Mulan [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Conli, R., et al., (Producers), & Greno, N., and Howard, B. (Directors). (2010). Tangled [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Del Vecho, P., Lasseter, J., and Scribner, A. (Producers), & Buck, C. and Lee, J. (Directors). (2013). Frozen [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Cottrell, W. et al. (Directors). (1937). Snow White and the Seven Dwarves [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C. et al. (Directors). (1959). Sleeping Beauty [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C., Jackson, W., and Luske, H. (Directors). (1950). Cinderella [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C., Luske, H., and Reitherman, W. (Directors). (1951). Alice in Wonderland [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C., Luske, H., and Reitherman, W. (Directors). (1961). One Hundred and One Dalmatians [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Geronimi, C., Luske, H., and Reitherman, W. (Directors). (1953). Peter Pan [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Reithernman, W. (Director). (1967). The Jungle Book [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Disney, W. (Producer), & Reitherman, W. (Director). (1963). The Sword in the Stone [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Disney, W. and Sharpsteen, B. (Producers), & Algar, J. et al. (Directors). (1940). Fantasia [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Giunchigliani, M. S. (2011). Gender transgressions of the pixar villains (Order No. 1507252). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1010773381). Retrieved from http://proxy.binghamton.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1010773381?accountid=14168

Hahn, D. (Producer), & Allers, R. and Minkoff, R. (Directors). (1994). The Lion King [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Hale, J. and Miller, R. (Producers), & Berman, T. and Rich, R. (Directors). (1985). The Black Cauldron [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Hall, B., & Almendarez, V. (n.d.). HOLLYWOOD, CENSORSHIP, AND THE MOTION PICTURE PRODUCTION CODE, 1927-1968. Retrieved April 27, 2020, from https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/archives-unbound/primary-sources_archives-unbound_hollywood-censorship-and-the-motion-picture-production-code-1927-1968.pdf

Honderich, H. (2019, April 8). Queerbaiting - exploitation or a sign of progress? Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47820447

Hutton, Z. (2018). Queering The Clown Prince of Crime: A Look at Queer Stereotypes as Signifiers In DC Comics’ The Joker. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. doi: 10.25148/etd.fidc006550

Mastro, D. E., & Greenberg, B. S. (2000). The portrayal of racial minorities on prime time television. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(4), 690-703.

Mattinson, B. and Miller, R. (Producers), & Clements, R. et al. (Directors). (1986). The Great Mouse Detective [Film]. Walt Disney Pictures.

Maverick22. Poll: Who is the Scariest Animated Disney Villain? [Data Set]. International Movie Database (IMDb). Retrieved from https://www.imdb.com/poll/yVSRCk4bc6k/results?ref_=po_sr

Kim, K. (2007). Queer-coded Villains (And Why You Should Care). Dialogues@ RU, 156-165.

Lago-Katyis, M., Lasseter, J., and Spencer, C. (Producers), & Moore, R. (Director). (2012). Wreck-It Ralph [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Mendoza-Pérez, I. (2018, October 26). Queer-Coding and Horror Films. Retrieved March 7, 2020, from https://controlforever.com/read/queercoding-and-horror-films/

Penner, E., and Disney, W. (Producers), & Geronimi, C., Luske, H., and Reitherman, W. (Directors). (1951). Lady and the Tramp [Film]. Walt Disney Studios.

Shafer, A., Bobkowski, P., & Brown, J. D. (2012). Sexual Media Practice: How Adolescents Select, Engage with, and Are Affected by Sexual Media. Oxford Handbooks Online. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398809.013.0013

Vujin, B., & Krombholc, V. (2019). High-voiced Dark Lords and Boggarts in drag: Feminine-coded villainy in the Harry Potter series. Зборник Радова Филозофског Факултета у Приштини, 49(3), 23–41. doi: 10.5937/zrffp49-23058

Watson, A. (2019, September 26). Disney - Statistics and Facts. Retrieved April 21, 2020, from https://www.statista.com/topics/1824/disney/